Dynamic Bytecode Execution for Fun and Profit

I’ve been reading into compiler engineering quite a lot recently (hopefully more posts to come on that in the future) and it occurred to me that I didn’t actually understand how dynamic code could be executed. My entire mental model of dynamic execution from a binary involved dynamic linking which is limited to what the program can accept since your host program still needs function declarations in order to perform that linking. It’s a far cry from the dynamic, generic execution of a runtime like the JVM’s JIT compiler.

Stack Smashing

My earliest exposure to executing code dynamically came from reading about return-oriented programming exploits around buffer overflows for binary exploitation. In modern compilers, there are protections baked in like randomized stack cookies for halting the program if stack smashing is detected and making the stack non-executable by default. LiveOverflow has a series of videos covering binary exploitations of this nature.

The general concept here is that the stack pointer is pushed onto the stack at the start of a vulnerable function, then a buffer is read into without protections to prevent overflow. If the attacker passes data into the program that is sufficiently long, you can overwrite the pushed stack pointer such that the program will execute at a new location. If you have a sufficiently large buffer allocated for the read data or a sufficiently small exploit, you could even put code compiled for the target platform into that buffer.

There are two mitigations for this:

- The stack is not executable by default. You can verify this for yourself with

readelf. On Linux, you can check ELF binaries withreadelf -l <PATH_TO_BIN> | grep -1 GNU_STACKwhich will show the stack asRW(readable and writable). - Stack cookies. This is a piece of data pushed to the stack at the beginning of a function which is not externally visible. Before the function returns, it also checks that the stack cookie has not been altered, and if it has been (indicating an attempt to overwrite the stack pointer) then the program terminates.

Allocating Executable Memory

I came across an old blogpost from burnttoys which demonstrated how to allocate memory which is executable, write machine code into the buffer, and then cast to a function pointer in order to execute that code.

Here’s the snippet:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

typedef unsigned (*asmFunc)(void);

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

// probably needs to be page aligned...

unsigned int codeBytes = 4096;

void * virtualCodeAddress = 0;

virtualCodeAddress = mmap(

NULL,

codeBytes,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC,

MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_PRIVATE,

0,

0);

printf("virtualCodeAddress = %p\n", virtualCodeAddress);

// write some code in

unsigned char * tempCode = (unsigned char *) (virtualCodeAddress);

tempCode[0] = 0xb8;

tempCode[1] = 0x00;

tempCode[2] = 0x11;

tempCode[3] = 0xdd;

tempCode[4] = 0xee;

// ret code! Very important!

tempCode[5] = 0xc3;

asmFunc myFunc = (asmFunc) (virtualCodeAddress);

unsigned out = myFunc();

printf("out is %x\n", out);

return 0;

}

The instructions are the hexadecimal literals which are loaded into tempCode. I wasn’t sure what they did and didn’t care to disassemble them to figure it out, but we just inject some of our own compiled code! But first I wanted to convert the program to Rust:

use libc::{c_void, MAP_ANONYMOUS, MAP_PRIVATE, PROT_EXEC, PROT_READ, PROT_WRITE};

fn main() {

const PAGE_SIZE: usize = 4096;

let virtual_code_addr = unsafe {

libc::mmap(

0 as *mut c_void,

PAGE_SIZE,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC,

MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_PRIVATE,

0,

0,

)

};

println!("Code address: {virtual_code_addr:?}");

let virtual_code =

unsafe { std::slice::from_raw_parts_mut(virtual_code_addr as *mut u8, PAGE_SIZE) };

let bytecode: [u8; 4] = [0x8d, 0x04, 0x37, 0xc3];

virtual_code

.into_iter()

.zip(bytecode.iter())

.for_each(|(virtual_addr, byte_code)| {

*virtual_addr = *byte_code;

});

let func: fn(u32, u32) -> u32 = unsafe { std::mem::transmute(virtual_code_addr) };

let out = func(40, 42);

println!("Out: {out}");

}

You’ll need libc = "0.2" as a dependency in order to build and run this. The first thing to note is naturally there is a lot of unsafe here! You are running arbitrary code in this manner and you’d really better make sure you know what you’re doing or else you could have a binary exploitation that’s taking over your host program.

Let’s take a quick look at where our executable memory comes from. We’re using mmap here which maps a region of memory into the process’s virtual address space. Nominally you can do this with a file and that memory might be shared between multiple processes that might be reading that file. In our case, we’re passing the flags MAP_ANONYMOUS and MAP_PRIVATE to indicate that the memory is not backed by a file and that the bytes written into this memory are not visible to other processes, respectively. (see the manpage for mmap). We also have to mark the memory as readable (PROT_READ), writable (PROT_WRITE), and executable (PROT_EXEC).

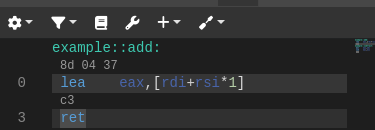

I swapped out the bytecode from burnttoys example with a simple add function. But where did I get the bytecode from? In Compiler Explorer, you can see the mapping of Rust (or other languages) source code into compiled assembly in the right-hand editor pane. If you click the little gear icon and check the box “Compile to binary object”, it will show the hexadecimal bytecode representation for each instruction.

This yields the four bytes for the function I implemented above. However, notice that I still needed to cast to a type and I knew the arguments and return type for that function pointer out-of-band:

let func: fn(u32, u32) -> u32 = unsafe { std::mem::transmute(virtual_code_addr) };

This makes it a far cry from being able to execute arbitrary code. But in the context of a JIT compiler, you’ll naturally have this information as you’ve just parsed the source or byte code for that function. And indeed, if you check out the source for the WebAssembly runtime wasmtime, you’ll see similar calls being employed.

Another interesting instance where this is used is in emulators where rather than interpreting all of the ROM’s code, they’ll recompile it just-in-time from, say, ARM32 to x86-64. Here’s a blogpost from a developer of melonDS discussing their JIT recompiler implementation.

Removing Guards

Finally, in case you’re really curious, you can actually tell rustc (or the linker, rather) that you’d like your stack to be executable. This is most definitely a code crime and should not be done in production code. In .cargo/config.toml,

[build]

rustflags = ["-C", "link-args=-Wl,-z,execstack"]

And then add this to the bottom of the Rust implementation above:

// Execute directly from the stack

let bytecode_ptr = bytecode.as_ptr();

let func: fn(u32, u32) -> u32 = unsafe { std::mem::transmute(bytecode_ptr) };

let out = func(40, 42);

println!("Out: {out}");

Conclusion

This was a short post, but I hope it was interesting and shed some light on some programming techniques that many developers probably haven’t come across before! You never know when having a little bit of understanding of the low-level depths of your tools can help when you’re building on top of them.

If you notice a dead link or have some other correction to make, feel free to make an issue on GitHub!