Megabit as an Embedded WebAssembly Display Prototype

A WebAssembly retro-display.

I’ve been taking a sabbatical for the past three months, and it’s been giving me a good bit of time to explore a technology that’s piqued my interest: WebAssembly! This article talks over my motivations and current results for executing WebAssembly in an IoT edge device.

All of the code referenced in this post can be found in this repository.

Background

I initially caught the WASM bug when I had a need to turn a CLI tool into a more friendly tool at AMP Robotics and I was able to put together a quick prototype as a single page web app. Then at SmartThings, the Hub device used Lua drivers to support different product families and protocols, and due to some limitations of Lua there was a lot of interest in WebAssembly from engineers there for a host environment that could run on this embedded Linux platform.

Fast forward to my sabbatical and I was looking for a project large enough to fit the amount of free time I suddenly found myself with! I was looking for something that would span a few different software components: both bare metal and embedded Linux, plus maybe more including an Android app. Thanks to the advertising apparatus of the internet, I stumbled across my inspiration: Tidbyt.

Tidbyt is an excellent little device which allows writing applications to control a 64x32 pixel display. The algorithm was correct to advertise it to me, it’s right up my alley. If this sounds cool, you should buy it and support them. I have just one problem with it: all running of the app and rendering happens in the cloud, which makes it difficult to show data from a homelab on the screen and means the device is essentially a brick if you lose network access. It’s totally understandable that the device would have these limitations, but I wanted to do even better.

Megabit

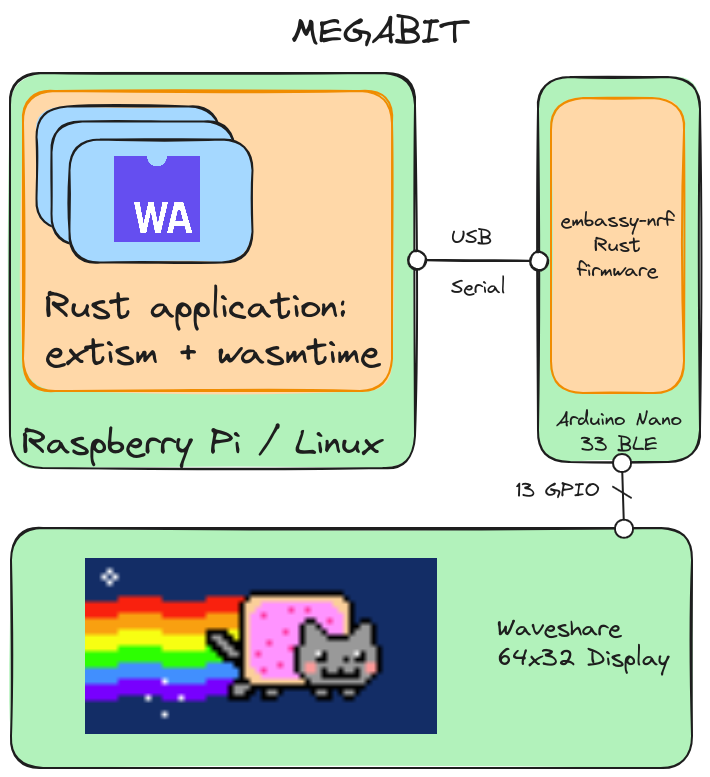

In order to render and run applications locally, I’d need more processing power and that meant embedded Linux. Linux wouldn’t be able to effectively drive these displays though, so that adds on an embedded coprocessor. The current system looks a bit like this:

WebAssembly Runtime

My go-to language for systems software is Rust and luckily there’s great support for WebAssembly tooling and libraries in Rust! In particular, I’m making use of extism which adds some convenient wrappers around wasmtime’s API (in multiple languages other than Rust in fact). Later, this simplifies writing apps as well.

The runner looks in a specific directory for application manifests which are JSON files which it uses to load the *.wasm binary along with some parameters like how frequently to run the application. Once it’s loaded each of them, it selects one to run and starts running! The currently running app can be cycled through with a button connected to the coprocessor.

The runtime’s control of the app is pretty straightforward, there are currently two entrypoints: setup and run. The setup function is called once when the app is switched to (I may re-evaluate this later so it doesn’t run it again if you cycle all the way around). The run function is called periodically as configured by the app’s manifest.

The runtime allows applications to import a number of APIs related to updating an in-memory copy of the color data on the display and getting information about the display. This currently includes a monocolor rendering mode and an RGB555 color rendering mode. In the future I’d like to add an 8-bit paletted rendering mode to decrease the size of serial payloads.

WebAssembly Apps

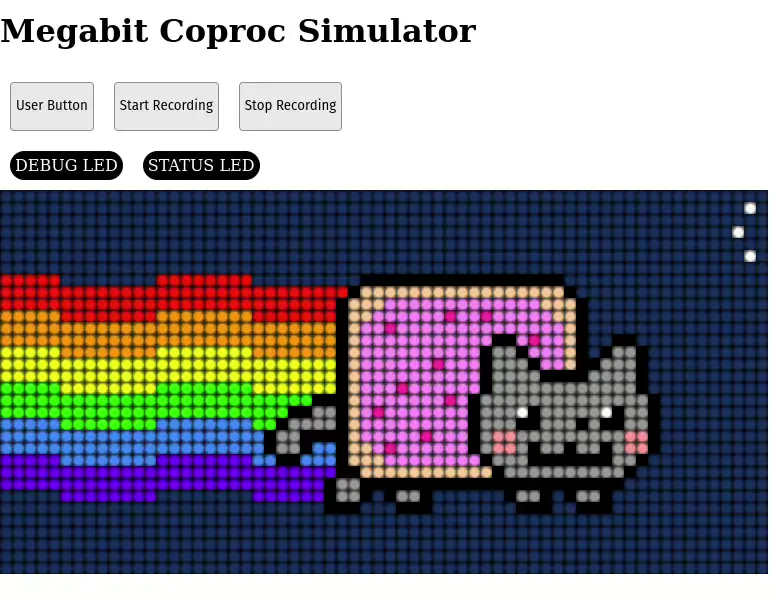

(note: if you’re on Safari, this animation renders very slowly)

(note: if you’re on Safari, this animation renders very slowly)

Any language which can target WebAssembly can be used to implement apps for Megabit (in contrast to my inspiration which runs Starlark apps). The bindings can be kind of tricky to set up for guest languages which are more high-level like JavaScript, but that’s where leveraging extism comes in handy to generate easier to use wrappers to handle passing of more complicated structures over the guest-host boundary.

I’m primarily focused on making Rust applications easier to write since that’s what I primarily develop in and to this end I also added a trait MegabitApp and a proc-macro to make the whole thing easier, here’s an example with a scrolling test app:

use extism_pdk::*;

use megabit_app_sdk::{megabit_wasm_app, MegabitApp};

#[megabit_wasm_app]

struct ScrollingTextApp {

display_cfg: DisplayConfiguration,

}

impl MegabitApp for ScrollingTextApp {

fn setup(display_cfg: DisplayConfiguration) -> FnResult<Self> {

if display_cfg.is_rgb {

display::set_monocolor_palette(Color::RED, Color::BLACK)?;

}

Ok(ScrollingTextApp { display_cfg })

}

fn run(&mut self) -> FnResult<()> {

// --snipped--

}

}

Behind the scenes, this generates some functions which actually map across the host-guest boundary, sets up a singleton for the struct which implements the trait, and handles calling methods on that singleton instance.

Additionally, the megabit_app_sdk crate offers some utilities to make drawing to the screen a little easier including a couple of structs which implement embedded_graphics traits for different screen rendering modes.

Coprocessor Firmware

My initial plan for this project had actually been to implement the coprocessor firmware in C++ with ZephyrRTOS, but after a couple weeks of frustration with that ecosystem, I embraced the meme and rewrote what I had in Rust using the newly stable embassy ecosystem.

It’s actually been a dream so far. I initially was working with a 32x16 display which only supported on or off states for each pixel and I managed to turn almost the entire firmware into a library which had no knowledge of the target hardware, only using embedded-hal and embassy-hal. Once I got the Waveshare display, I was able to quickly write a new main function which initialized all the hardware, making changes to which pins were used for different hardware resources, and then I was off and running on testing the new screen.

Embassy is a framework built around executing async Rust on embedded targets and for the most part that’s been smooth sailing and naturally fits the event-driven nature of an embedded system that’s waiting for commands over USB. I ran into some problems when it came time to write the driver for the display, which occasionally needs small delays to not overwrite certain signals too quickly. I added some asynchronous delays with Timer::after_micros(1).await and quickly found that the number passed there is a lower bound. It was sometimes taking on the order of 350 microseconds to wait for what I thought would be 3 microseconds!

That makes sense, as the executor does not necessarily favor the driver task futures over other futures and the task-switching overhead is not zero, but it means that I had to switch those for assembly-based delays like cortex_m::asm::delay(50). Even so, updating the entire display (which has to be done repeatedly for all time) takes around 27 ms and I had to add an asynchronous wait between refreshes so I didn’t starve my other tasks. This means the firmware actually only gets 5 ms windows to address incoming USB commands!

Conclusion

My experience digging into WebAssembly so far has been great. I used Rust to execute my runtime and Rust developers are spoiled with good WebAssembly tooling, but the whole process feels very smooth, even when using relatively new features like WASI!

When I first started in on this project I was envisioning apps following a permissions model like an Android app, where fine-grained permissions to host resources are exposed to properly sandbox apps. The ecosystem is not currently there, but not because it’s held back technologically, it’s only missing the effort to build out the necessary APIs around existing runtimes like wasmtime in order to selectively stub some specific parts of WASI with a SandboxPermissionDenied returning function or something of the sort. I think fine control like this likely develop soon as it’s useful not just for edge devices where you want to keep things from snooping on your local network, but also in cloud environments where you want to limit which domains or IP addresses an app might be accessing. I see some upcoming talks at WasmIO 2024 discussing this very feature.

An additional pain point that I’m stumbling on is utilizing async in apps. wasmtime supports asynchronous execution, but it seems to require making all of the APIs exported to the host async, and the complication of supporting the Rust async model across multiple languages means that convenient wrappers like extism become more difficult to implement, maintain, and use in a consistent way. One way I’m currently envisioning circumventing this is simply adding an additional entrypoint API which allows the host to “warn” the guest environment of an incoming cancel if it doesn’t complete. I think this willl allow the host to cancel misbehaving apps while being tolerant of an internally running async executor.

As a reminder, if you’re curious about the code, it can be found here.

If you notice a dead link or have some other correction to make, feel free to make an issue on GitHub!